❤️📊 When should you commit?

I started thinking about commitment not as an emotional decision, but as a sequential decision problem.

Many real-life situations share the same structure: dating, hiring, career moves.

You encounter options one at a time, decisions are irreversible, and you don’t know what lies ahead.

So I framed a simple (and very unrealistic) thought experiment.

Problem Setup

Assume the following:

- You will encounter (N) options sequentially

- The order is random

- You can only rank the current option relative to those already seen

- Once an option is rejected, it cannot be recalled

- The goal is to maximize the probability of selecting the best option

The question is not which option to choose —

but when to choose.

A Simple Strategy: Observe, Then Commit

Consider a two-phase strategy:

-

Observation phase

Reject the first (r) options unconditionally

(used only to calibrate what “good” looks like) -

Selection phase

From option (r+1) onward, select the first option that is better than all previously observed options

The key question becomes:

What is the optimal value of (r)?

Mathematical Derivation

Let:

- Total options = (N)

- Observation window = (r)

- Best option overall = (B)

Conditioning on the position of the best option

Suppose the best option (B) appears at position (k > r).

You will select (B) if and only if the best option among the first (k-1) appeared within the observation window.

The probability of this event is:

$$ \frac{r}{k-1} $$

Since the best option is equally likely to appear at any position:

$$ \mathbb{P}(B \text{ at position } k) = \frac{1}{N} $$

Total probability of success

Summing over all valid positions:

$$ P(r) = \sum_{k=r+1}^{N} \frac{1}{N} \cdot \frac{r}{k-1} $$

This can be rewritten as:

$$ P(r) = \frac{r}{N} \sum_{k=r}^{N-1} \frac{1}{k} $$

The sum is a truncated harmonic series.

Large-(N) Approximation

For large (N), the harmonic sum satisfies:

$$ \sum_{k=r}^{N-1} \frac{1}{k} ;\approx; \ln\left(\frac{N}{r}\right) $$

Substituting back:

$$ P(r) \approx \frac{r}{N} \ln\left(\frac{N}{r}\right) $$

Optimization

To find the optimal stopping point, maximize (P(r)):

$$ \frac{d}{dr} \left( \frac{r}{N} \ln\left(\frac{N}{r}\right) \right) = 0 $$

Solving this yields:

$$ \frac{r}{N} = \frac{1}{e} $$

Final Result

- Optimal observation fraction:

$$ r \approx \frac{N}{e} $$

- Maximum achievable success probability:

$$ P_{\max} \approx \frac{1}{e} \approx 0.37 $$

Even with a perfect strategy, the probability of selecting the best option is fundamentally bounded.

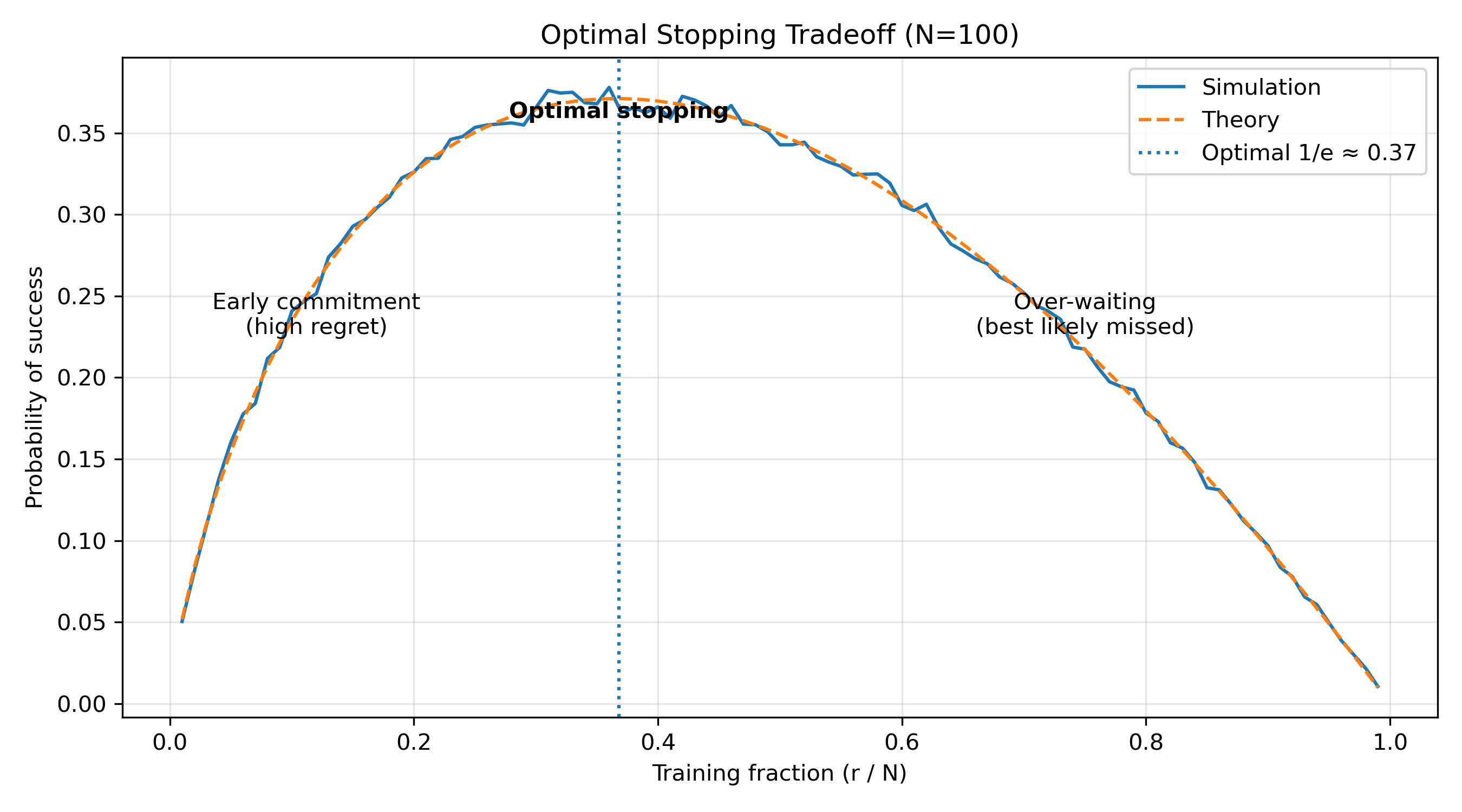

Monte Carlo Simulation

To verify this result empirically, I ran Monte Carlo simulations:

- Option quality modeled as a latent total ordering

- Arrival order sampled uniformly at random

- The observe-then-commit strategy applied for different values of (r)

- Success measured by selecting the global maximum

Simulation Result

The curve clearly shows three regimes:

- Early commitment — insufficient information

- Optimal stopping — peak near (1/e)

- Over-waiting — best option likely already passed

As (N) increases, the empirical results converge tightly to the theoretical prediction.

Interpretation

Although motivated by a dating-inspired thought experiment, this structure appears directly in:

- hiring decisions

- candidate screening

- investment timing

- irreversible career choices

The core insight is not about choosing better options, but about choosing at the right time.

Closing Thought

Real relationships are far richer than any mathematical model.

But as a way to reason about irreversible decisions under uncertainty, this framework is surprisingly powerful.

Sometimes the hardest part isn’t choosing —

it’s knowing when to stop looking.